The Flower Power carnival of LSD, DayGlo paint and youthful indiscretion, better known as the Summer of Love, came and went in 1967. The Manson Family hippie-cult massacres in Hollywood, followed closely by murderous violence at the Altamont Free Concert, ruined everyone’s high in 1969.

My own romantic attachments to the Age of Aquarius though ended on Jan. 22, 1972, when my father, Andy Kinyon, was found stabbed and slashed to death in San Francisco’s bohemian North Beach. He was just 29. And the killer — or killers — were never brought to justice.

I was 9 years old when it happened. I remember adults acting strange around me, waiting for a reaction. My dad was never coming back, and there was nothing I could do to change it. I knew I was supposed to cry. My mom and little sister were crying. What was wrong with me? The only thing I could feel was guilt for not feeling anything.

I clipped the story from the now-defunct Palo Alto Times and took it with me to school. When my classmate Sherry read it, she began bawling and ran away. I felt even more guilty. Something told me that I’d cry — eventually — just not now.

A week after the crime, homicide inspector Frank Falzon called my mom to let her know they had arrested someone and took their knife and blood-spattered boots into evidence. “The knife was boiled clean,” he told her, “and the blood on the boots was covered up with shoe polish.” Falzon said he was doubtful that the lab would be able to type the blood and match it to Andy. “Without that, we’ve got no case,” he added.

The suspect, Eugene Santore, was allowed to walk.

My dad conducted liquid light shows for Bill Graham … [but] retreated to North Beach when the scene was overtaken by homeless wannabes, pimps and speed dealers.

I remembered Gene hanging out the past two summers that I spent in the city. He wasn’t like my dad’s other friends. He wasn’t cool. He was always having a bad day. He hated me because he had to vacate the guest room so that I could use it. The creep glared at me every time he saw me. Later, I’d glare back at him. He left the room infested with head lice that first summer, and I had to shave off all of my hair. Third grade had not been easy looking like a cult member.

Gene hated me for no reason. I wondered if that same blind hatred led him to kill my dad.

My mom withdrew to her bedroom. She curled up in a ball and sank into deepening despair. Days went by, and then a week. She wouldn’t leave her bed. My sister, Lori, and I did our best to comfort her. We brought her food. Lori brushed her hair. I fluffed up the pillows for her. While we were away at school, our stepdad Rod introduced her to heroin.

As soon as she was on her feet, Mom pulled me into the Impala and we headed up to my dad’s place. The bartender, Neil, who worked the Camel Bar on the ground floor, showed us exactly where he found Dad’s body on the stairs. We carefully avoided the spot where he died and began our ascent to the penthouse flat.

I thought back on the wonderfully adventurous times I had living with my dad over the summer. I knew those memories were going to have to suffice for the rest of my life. I swore to myself that I’d never forget them.

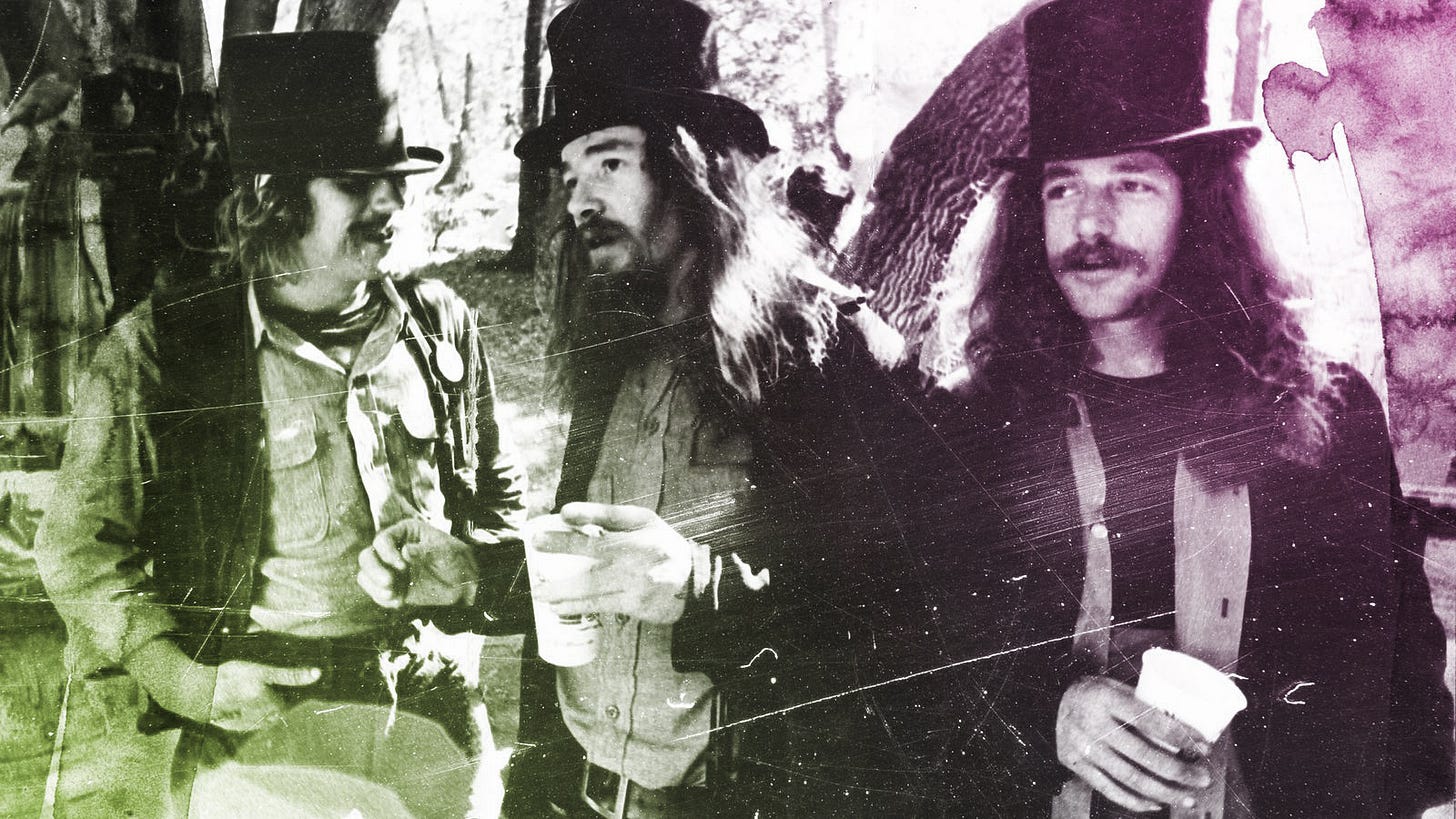

Gary “Bananas” greeted my mom with his patented bear hug. He was my dad’s best friend and the roommate with the longest tenure at the notorious Grant and Green crash pad. The two became tight when they were fixtures in the Haight. My dad conducted liquid light shows for Bill Graham and The Family Dog. Gary was a popular pot dealer and former roadie for Jefferson Airplane and Big Brother & The Holding Company. They retreated to North Beach when the scene was overtaken by homeless wannabes, pimps and speed dealers.

Gary handed me a copy of Zap Comix #5 to keep me busy, then took my mom aside. He told her what he told the cops: He was sitting by the living room window and noticed Eugene walking up Grant Avenue. He says he watched him enter the gate of their apartment building at the time of the murder. “He did it. I know he did it,” Gary said angrily. “He’s a fuckin’ psychotic, and he’s been after Andy for months.”

My mom called Detective Falzon every week to see if there were any new leads or breaks in the case. He’d always tell her, “Nope, nothing new.” A few times he asked her if she was seeing anyone and if she’d like to go out on a date. She’d politely decline, then call again the following week, only to repeat the same routine.

She was home alone taking a shower one morning when someone began banging hard on the bathroom window. She thought they’d break the glass. As she quickly slipped into a skirt and blouse, the loud banging started up again, this time at the front door.

“Something clearly stinks in how police handled this case.”

Tony Serra, famed civil rights attorney

“Open up! It’s the police!”

Slowly cracking the door open, she saw two Palo Alto Police officers glaring at her.

“Geraldine Kinyon?”

“Yes, that’s me.”

“San Francisco Homicide lost your phone number and they need you to call them, immediately.”

She ran to the phone thinking there may be good news regarding the case. In her excitement, she misdialed twice but finally pulled it together. Falzon picked up.

“Geri, we need your help. We have a guy here in the psych ward who has confessed to killing someone with a knife in North Beach.”

“Oh, my God, you got him?” she asked. “It’s not Eugene, it’s someone else?”

“Could be, could very well be. Do you know his name?”

“How would I know his name?”

“He says that the wife of the man he killed was in on it.”

“Excuse me?”

“Are you denying you were involved, Geri?”

“Why? What … what are you saying?” She was shocked and stunned at the insinuation. Her knees began to weaken. She collapsed in a chair and began sobbing. Falzon wrapped up his call. Thinking back on this years later, she felt the entire episode was designed to get her to back off. But for more than 10 years, my mom checked in on my dad’s birthday. Every time she was told that nothing had changed and that they didn’t have enough evidence to charge Santore. “We know he did it, we just can’t prove it,” was the refrain.

In 1984, Falzon told my mom that he finally had some good news. He told her that Santore had been “convicted of a similar crime” in New York and that he wouldn’t be getting out of prison anytime soon. He told her to take comfort in that. He also told her to stop calling, saying, “If anything changes, I’ll make sure you’re the first to know.”

A consolation prize was not what we were looking for.

Mom flew to New York City in 1985 to visit relatives. While there, a thought hit her: Why not talk to Eugene Santore face-to-face? She dialed up the New York State Department of Corrections and inquired about Santore, believing that he was in prison. They told her that there had never been a person by that name in their system, ever.

It was like a bomb went off, blowing a hole in everything. If he wasn’t in prison, then where was he? And, if he had never been in prison, why would Falzon lie to us? None of the implications were good.

In the winter of 1989, Lori and I made a pilgrimage to the scene of the crime. We stood silently at the foot of the stairs where our dad met his end. The new tenants let us into his old room. We climbed out onto the roof. The view of the San Francisco cityscape at night was breathtaking. Strangely, I couldn’t catch my breath. I thought I was having a heart attack. A softball-sized lump worked its way up from my chest to my throat. I couldn’t hold it in, I burst out in tears. It was about time.

In 1993, we heard that DNA testing was now being used to solve murder cases. We requested that the knife and boots be run through the process. After some heavy foot-dragging, Falzon told us that the knife and boots had been sent in but that there wasn’t enough blood to test.

A small flicker of hope had extinguished. Was this case ever going to be solved? It had been 20 years and we had nothing but unanswered questions. If the killer was convicted, there was at least a chance that we’d find out why he did it. Was Andy killed following a bar fight? Was it over a woman? Was it revenge? Or was it just mindless violence?

Most stunning of all the truths we absorbed that day was the jaw-dropping revelation that Eugene Santore was not the actual name of the main suspect … his real name was Eugene Imbrogno.

Not knowing has been absolutely devastating. It’s affected everything about me. It’s touched every aspect of my life — my social interactions, every single relationship, every friendship, every chance meeting have all been affected or damaged in some way. I grew up not being able to trust anyone. For all I knew, my dad trusted the person who gutted him with a knife and slashed his throat. If I broke up with a girlfriend, would she flip out on me? Or would her new boyfriend? If I start dating someone new, will an ex-lover show up and take me out? When I’m out in public and bump into a stranger, am I about to be fighting for my life?

Fast-forward yet another decade: Detective Joe Toomey was assigned to our dad’s case around 2007. Lori called him to see if he might send in the blood evidence for DNA testing since major advances had been made over the years. He said that it was a waste of time. She went down in person and asked him again. He refused. She asked him if we could arrange a meeting to review Andy’s case file for the first time. Toomey told her flat-out, “No, you can’t.” She asked him why, he responded, “Because I said you can’t.”

By the time she got home, Lori was seriously pissed. She left Toomey a message. It wasn’t returned. She called the next day and the day after. Then she began a campaign of faxing him letters and leaving daily voicemails. She was relentless. She was not going to be ignored. Toomey finally called her back, “Listen, lady, if you don’t stop calling, I’m going to lose your dad’s case file, do you understand me? I will lose the file, and no one will ever see it again.”

In 2010, our family was notified that our dad’s case had been moved to a brand-new Cold Case Unit at the SFPD. Holly Pera was the detective in charge. We contacted her immediately, and she told us that she’d gladly sit down with us and go over the evidence in the case file.

We were excited. We were scared. We were not prepared for what we would find.

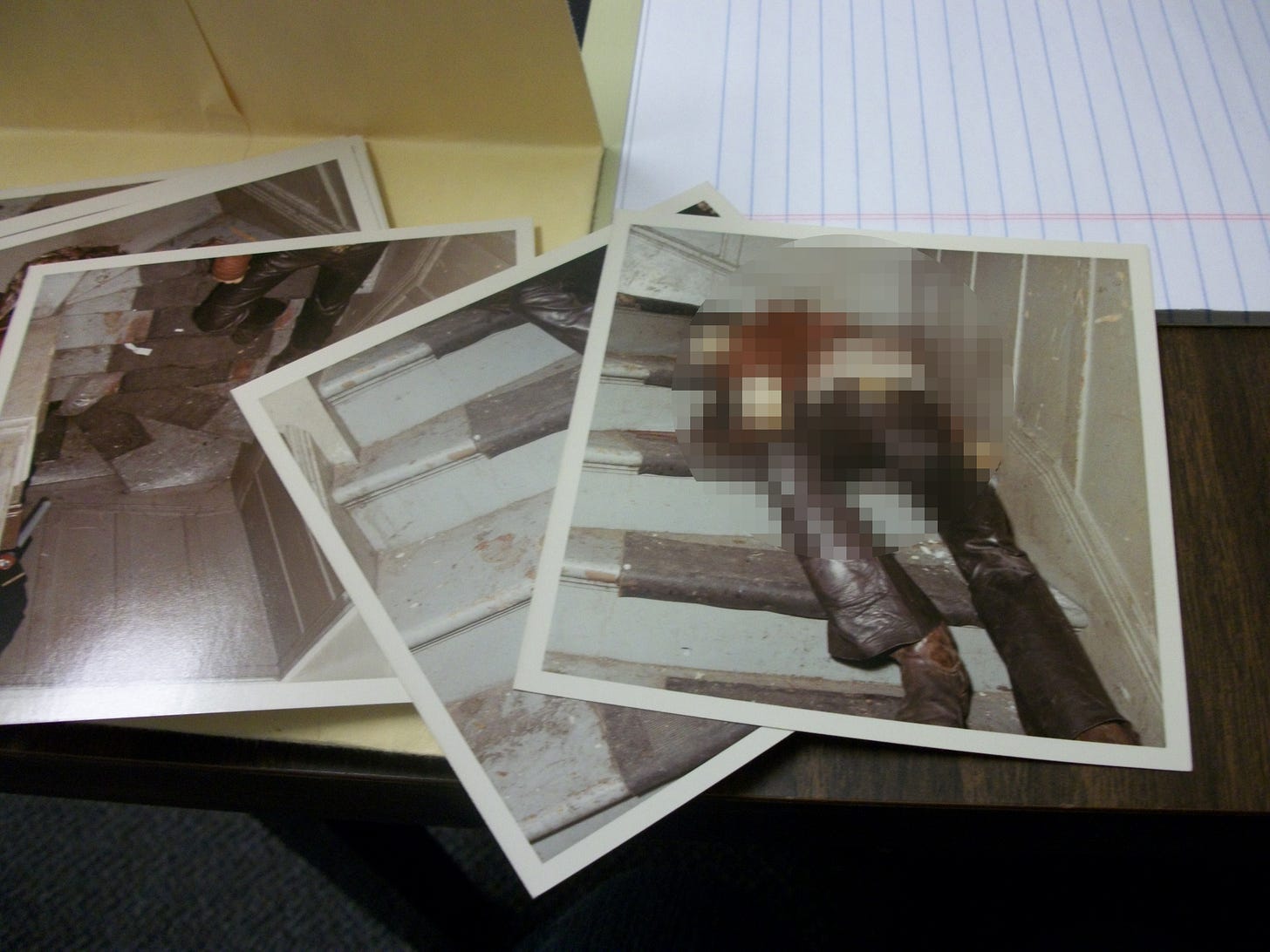

Two manila folders contain the evidence gathered by detectives Frank Falzon and his partner Jack Cleary. It was startling to see just how little work had been put into the investigation. Not one item had been added after the first couple of weeks. No notes. No follow-up on leads. Nothing.

As we pored over the scant collection of witness statements, police reports and crime-scene photos, a clear story came together: There was an extremely strong case against the main suspect.

In the months leading up to his death, Andy was being strong-armed for money by two Italian males. One of them was reportedly Eugene Santore. After a particularly bad beating, Andy borrowed money from his neighbor Shig Murao, telling him, “I can’t fuck with these people.”

My dad and his girlfriend, Margery King, attempted to burglarize a leather shop in December, just a month prior to the murder, but they got busted. This must have been a last-ditch attempt to raise cash. After they failed, Andy told Margery that he was going to be killed in January.

At the time of the murder, a neighbor heard the assailant yell repeatedly, “You bet you’ll pay!” There was so much evidence pointing to the guilt of the main suspect that it became more and more unnerving with every new turn of a page.

The statement Santore gave detectives contained several lies. Most importantly, his alibi was shot down by the very friends he claimed could prove he was not in the neighborhood at the time of the crime. His friends surprisingly told detectives that they left him standing on the very block that the murder took place, approximately 20 minutes before it happened. One of them even volunteered that Santore was extremely upset about something at the time.

Most stunning of all the truths we absorbed that day was the jaw-dropping revelation that Eugene Santore was not the actual name of the main suspect. Over the past 38 years, detectives at SFPD Homicide referred to him only by his alias, when his real name was Eugene Imbrogno.

Holly couldn’t tell us if this man was dead or alive. She pulled up his impossibly long rap sheet and pointed out that his last run-in with the law was in Florida, back in 1983. She wondered if it was possible that he had retired from his life of crime. I stated the obvious: A man as violent as this guy would never be able to fly straight and stay out of trouble. She agreed.

A closer look at Imbrogno’s record revealed that he was not presently locked away “for a similar crime” in a New York prison, nor had he ever been.

We left the meeting angrier and more confused than we were at the beginning. We were also more determined than ever to track this guy down. Three days later I found him, buried at Valley Memorial Park in Novato. His obituary states that he died after a short illness in 1984 at his residence in Fairfax, just across the Bay from San Francisco.

I emailed the obituary to SFPD Homicide. I thought they might like to know.

I launched a private investigation eight years ago, armed with names and evidence found in the case file. Not too surprisingly, all of my dad’s close friends, his roommates and the witnesses who gave statements to the police are no longer with us. A few of these people I missed finding alive by just a year or two — 46 years is too long to allow a trail to go cold. It pains me to think of what I could have uncovered if only we had been told the truth early on. Still, I’ve been able to turn up some unbelievably crazy shit.

On the day that Imbrogno was brought in for questioning, he was discovered sitting in a car across the street from the scene of the crime. The man in the car with him was a prominent North Beach businessman with deep ties to the San Francisco crime family, also known as the Lanza crime family. In fact, this man’s lineage goes back several generations, not only to founding members of the mafia in San Francisco but to the early bosses in the Milwaukee Mob and the Chicago Outfit.

A thought crosses my mind: Perhaps the cops lied to us to protect us.

This has become almost too crazy for words, but I thought I’d try.

R.I.P., Dad.

Originally published NOVEMBER 25, 2018 by now-defunct Ozy Media

BOOK OUT NOW!

Get your copy now at AMAZON - Paperback and Kindle editions available.

Never trust an ex-school bully with a gun and a badge.

The book was finally published!

Available now: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B0BZ6QH1BP